Since the dawn of the Industrial Age, humans have significantly altered all of Earth’s systems through human-environment interactions. Sadly, almost all of these changes have resulted in extreme environmental degradation.

In the 21st century, the negative effects of environmental destruction brought about by the interplay of social and planetary systems (physical, ecological, and biological) are catching up to humans. Our climate crisis is becoming more severe. People are experiencing it through widespread drought, flooding, heatwaves, polar vortices, and wildfires, just to name a few.

Soon, experts predict food and water shortages — largely due to our climate crisis — will strain already compromised global supply chains, wreaking catastrophic economic strife everywhere on Earth.

Over time, the changes to Earth’s systems wrought by humans lead to more — often unexpected — impacts on both the environment and human populations. And there are unanticipated shifts to these mutually affecting changes as well.

Human-environment interactions may suffer and worsen as a result.

Unfortunately, there is no end in sight as long as humans continue to burn fossil fuels.

In this article, you will find extensive descriptions of all the major types of human-environment interactions with plenty of examples of the ensuing environmental damage stemming from those interplays.

But you will also learn about a few cases in which human-environment interactions have been positive — for both humans and the environment.

Using these examples as starting points, it’s possible to recreate the future of human-environmental interactions such that more — or most — of them are mutually beneficial with only minimal environmental devastation.

The Anthropocene: an overview of human-environment interactions

In 2000, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul J. Crutzen and his esteemed colleague, ecologist Eugene F. Stoermer, popularized the term Anthropocene to describe a new geologic period on Earth.

Taken from the Greek language, “anthropo-” means human. “-Cene” refers to a new epoch in geologic time.

To date, there is no formal acceptance of this term by the scientific organizations which officially classify geologic time periods. There is, however, a lot of vigorous debate over the word among scientists and lay citizens alike.

Anthropocene has become mainstream, even trendy. Books, articles, podcasts, and videos about the Anthropocene are commonplace now.

What is the Anthropocene?

The word Anthropocene refers to humankind’s direct and indirect impacts on planetary systems including physical, ecological, chemical, and biological systems. These impacts are due to frequent and substantial human-environmental interactions.

Crutzen and Stoermer developed this idea of the Anthropocene based on data available to them in 2000. They cataloged a long list of human-environment interactions before announcing their concept. Based on these data, they placed the beginning of the Anthropocene at the end of the 18th century (late 1700s). To update their list found in the previously cited newsletter, here are more recent statistics on human-environment interactions:

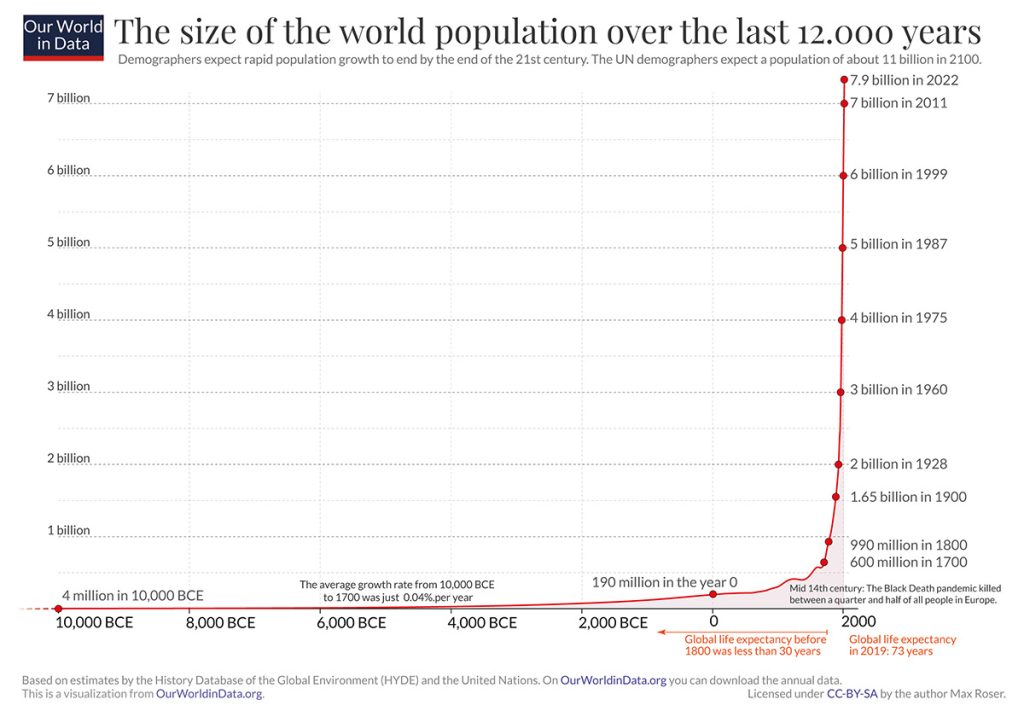

Human population growth

Over the last 12,000 years, almost all human population growth has occurred since 1800 when industrialization accelerated substantially. This date is used as a benchmark since it corresponds roughly to James Watt’s steam engine invention in 1784.

In 1800, the human population was approximately 1 billion. A little more than two centuries later, it has increased almost 8-fold to 8 billion people.

To place this in perspective: twelve millennia ago, the human population was about 4 million. Today, it’s around 2,000 times that number.

Here’s what it looks like:

The small print under the graph’s title states that United Nations demographers predict the human population will level off at 11 billion by 2100.

The burning question, however, in light of our climate crisis precipitated by human-environment interactions is: Will humanity survive to 2100?

All those people demand natural resources to live: food, water, clothing, shelter at the bare minimum. To extract those resources, people must interact with the environment.

Will there be enough to go around in 78 years? Babies born today will confront this issue during their lifetimes.

Fossil fuel consumption

Crutzen & Stoermer state that humans are consuming in a “few generations” the fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas) generated through decayed animal and plant matter. The decomposition process took over several hundred million years.

Counting back to 1800 — the approximate start of the Industrial Age — that’s equivalent to 10 generations (20 years = 1 generation).

The rapid consumption of fossil fuels — compared to how long it took to form them — results in a huge influx of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Like a blanket around the Earth, these gases hold in heat. The average temperatures of land and oceans increase.

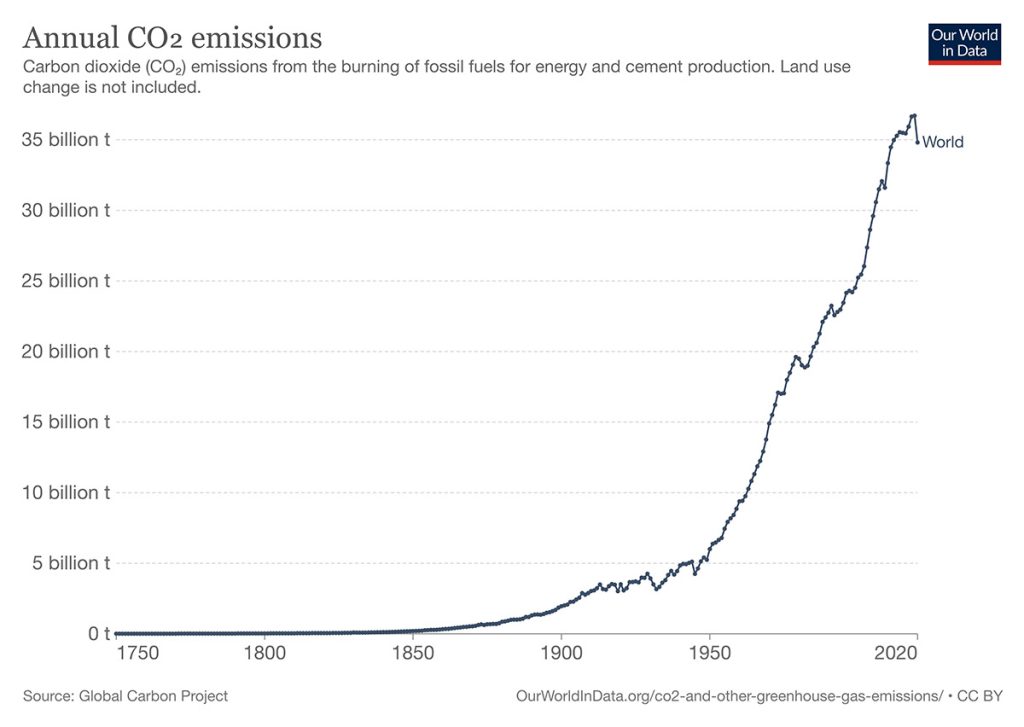

The major greenhouse gas released from the combustion of fossil fuels is carbon dioxide (CO2).

Historically speaking, the United States is the biggest emitter of (CO2).

The U.S. is responsible for about 25% of all CO2 emitted — ever — by humans. The U.S. is only 246 years old.

Although China overtook the U.S. in annual CO2 emissions in 2005, China is historically responsible for emitting only half as much as the U.S.

By the numbers on a global basis (CO2 emissions in tons):

- 1950: 6 billion

- 1990: 22 billion

- 2021: 36 billion

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the largest annual increase in carbon dioxide emissions occurred in 2021.

Apparently, the world rebounded from the Covid-19 lockdowns with fury.

Experts predict the peak in carbon emissions has not yet been reached.

Here’s a graphical interpretation of what carbon emissions resulting from fossil fuel burning looks like:

Land use changes

The way humans interact with the environment through land use is a dramatic illustration of how deep and wide the human footprint on the planet really is.

As Dr. Erle C. Ellis states in his 2021 article:

“By transforming Earth’s ecology, land use has literally paved the way for the Anthropocene.”

Dr. Ellis uses the term land use to refer to “human cultural practices that alter terrestrial ecosystems for a societal purpose…”

Land use includes:

- Conversion and fragmentation of native ecosystems

- Introduction of new animal and plant species to a region — many of which become invasive

- Soil and water pollution caused by land use altercations

Although this definition alludes to an apparent dichotomy between nature vs. culture, it is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the robust discussions on this supposed difference.

For sure, there is plenty of evidence for the dynamic interplay of cultural humans enmeshed in natural environments. The interactions — both positive and negative — are ongoing.

Suffice it to say for this article on human-environmental interactions that people transform the environment when they alter it for a reason related to human society.

Here are some Earth-shattering — pun intended (!) — statistics about land use:

- Up to 95% of ice-free land has been altered by humans since recorded history

- Today, land use is the major cause of biodiversity loss. Of the more than 40,000 species threatened or endangered, agriculture is a threat to at least 24,000 of them.

- Land use-associated greenhouse gas emissions were the #1 contributor to our climate crisis until the 1950s, when fossil fuel burning for energy became rampant

Massive land use changes for agriculture is the major “societal purpose” humans have engaged in for over 10 millennia.

What is astounding is that “only” one thousand years ago, less than 4% of the ice-free land surface was used for agriculture.

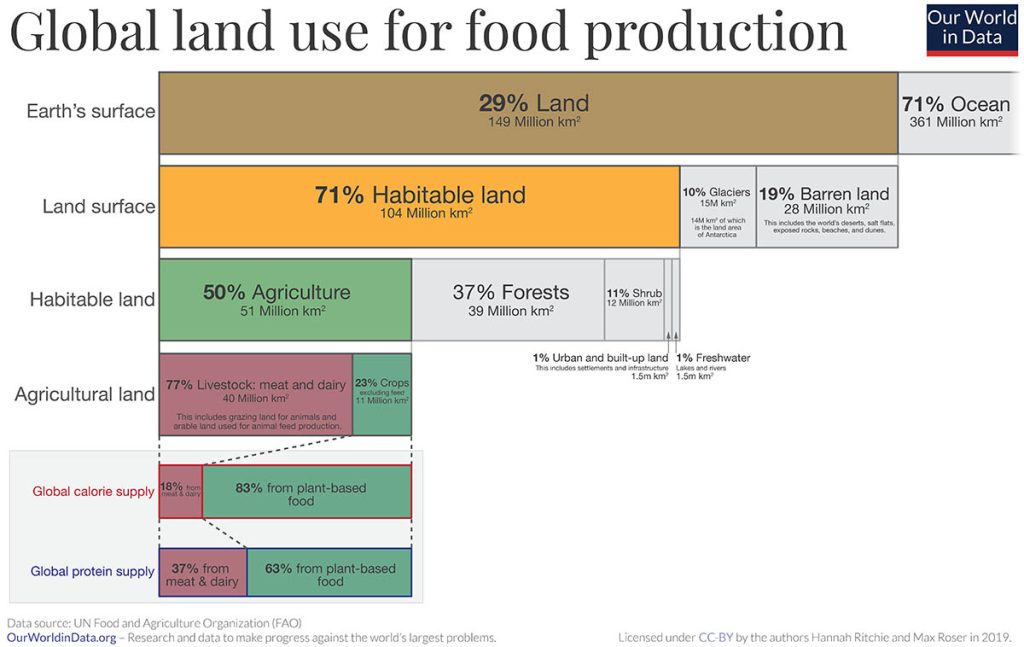

Today, half of all “habitable” land — excluding the 30% of Earth’s surface which consists of uninhabitable glaciers, deserts, rocks, etc. — is devoted to agriculture.

Of that agricultural land portion, almost 80% is associated with livestock (grazing, feed crops). Yet, that large segment yields only 18% of all the calories produced by agriculture. It represents merely 37% of all protein supplied by agricultural practices.

Here is a graphical illustration of land use devoted to agriculture:

Excluding agricultural land, here’s the breakdown of the rest of ice-free land:

- 37% forests

- 11% grasslands

- 1% freshwater bodies (rivers, streams, lakes)

- 1% urban areas

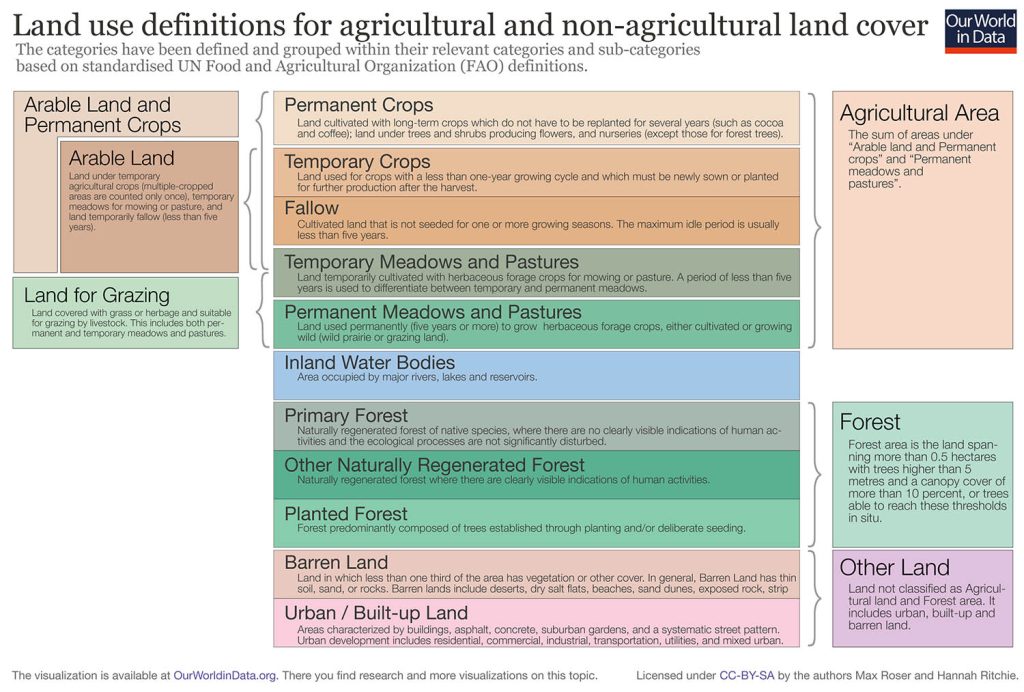

As an infographic with terms defined:

You may be surprised by the low percentage for cities and towns. The United Nations predicts urbanization will grow rapidly in the 21st century. In fact, 68% of the human population is expected to live in cities by 2050.

How long will the Anthropocene last?

Experts who theorize about the Anthropocene can only predict if and when this geologic epoch will end. Crutzen & Shoermer, the originators of this concept, state in their landmark writing that:

humans “…will remain a major geologic force for many millennia, maybe millions of years to come.”

That is, unless there is a major catastrophe that renders humans extinct such as:

- Volcanic eruptions

- Asteroid hitting Earth

- Nuclear war

- Pandemic (Incidentally, they wrote 20 years before SARS-CoV-2.)

Are you surprised by their projection of millions of years?

Keep in mind that most non-anthropogenic planetary shifts in temperature in response to changes in greenhouse gas concentrations occur very slowly on a geological timescale. (Although volcanoes and asteroids are special cases.)

So it is quite possible that the effects of certain human-environment interactions on planetary systems could last that long.

It’s mind boggling to think that what humans do today can affect the Earth for millions of years.

But it’s quite possible.

The power of nature in human-environment interactions

From the previous section, it’s clear that humans have heavily influenced the environment. People may think they are the masters of the universe when they survey the sheer scope and scale of how they have harnessed nature’s power to serve their own ends.

But that is just one side of the story.

Has the environment wrought its power over humans in any significant way? In other words, in coupled human-environment systems, does nature ever get the upper hand?

There is no doubt that the environment has — and continues to — affect humans and human societies significantly. In fact, the environment limits humans in important ways.

For example, one way to understand the notion of environmental constraint on humans is to consider natural catastrophes. The power of nature over humans becomes evident.

Here are a few cases of nature’s control over humans in human-environment interactions.

Fires in human environment interactions

Remember the massive grassland fire that seemed to erupt spontaneously at the end of 2021 in Boulder, Colorado, destroying one thousand homes and leaving monumental environmental devastation in its wake?

Source: Flickr / State Farm

Reasons offered to explain it describe the perfect scenario for this natural hazard to occur:

- Unusually wet spring promoted grassland growth

- Followed by prolonged drought in the summer

- Unseasonably warm weather in the fall prior to the blaze

- High, sudden winds when the fires erupted

Now cities and towns experiencing similar weather patterns — intensified by our climate crisis — must prepare for possible catastrophes like it — or pay a heavy price later in lives and livelihoods lost.

Flash flooding in human-environment interactions

Just as the fires whipped up rapidly in Boulder last year, numerous places around the globe experienced sudden onslaughts of water everywhere with little or no warning in 2021.

Germany. Brazil. China. To name just a few.

When the water is pouring in or seeping up from the floor, there is no escape.

In addition, there will be toxic mold issues to deal with later.

Source: Wikimedia / Bärwinkel, Klaus

Given the sheer power of nature, it comes as no surprise that scientists remain stunned at the flooding, coming up short on explanations.

Here are a few ideas to explain the flooding:

- Inadequate disaster preparedness plans focusing only on major waterways (not minor streams)

- Slow-moving storms that linger over flood-prone areas, gathering more moisture over time

- Building too close to rivers rather than maintaining broad floodplains (i.e., a human encroachment problem)

- Lack of public awareness about what to do upon hearing a flood warning

Except for the second reason listed above which is linked to our anthropogenic climate crisis, human hubris (false pride) has some role to play in explaining the flooding.

When people think they understand nature’s power, or think that nothing bad could happen to them in an affluent area, nature may surprise them about where the control really exists.

Environment: 1. Humans: 0 in this human-environmental interaction.

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and human-environment interactions

Although there is some dispute over the origin of the virus that causes Covid-19, it is true that microorganisms like bacteria and viruses can spill over (or cross over) from other animals — wild and domesticated — to humans.

Wildlife habitat encroachment by humans sets the stage for the crossovers to occur. The closer contact that ensues between other species and humans makes it easy for microbial jumps to happen.

Source: Wikimedia / LukaszKatlewa

Government leaders have been forewarned by virologists and public health officials about the real possibility of future pandemics. Unfortunately, politics tends to work in election cycles. The U.S. congress, for example, in April 2022, eliminated all global support for Covid-19 eradication from its budget.

The science is clear that pandemics will not end unless the entire world has resources to tackle them. Again, human arrogance or selfishness may result in a prolonged Covid-19 pandemic or a greater likelihood of future pandemics due to inaction today.

In this human-environment interaction, the environment (as represented by a virus) will have the final say unless humans act quickly and wisely.

Prolonged drought due to human-environmental interactions

The entire western half of the United States is experiencing an extended, severe drought. Not only is California, a major agricultural state, affected.

Source: Don DeBold

The drought is spreading eastward, making growing conditions in the country’s breadbasket (the Midwest) also difficult.

The extreme, persistent dryness lengthens and expands the wildfire season.

Here are some examples of the controlling effects of drought:

- Food prices are expected to rise significantly this year

- Tourism plummets

- Ski resorts have shorter seasons (unless they make artificial snow which is costly)

- Residential wells dry up

- Water wars between farmers, ranchers, and residents

- Subsidence (land sinking due to underground water table falling from over-irrigation)

The problem of water scarcity coupled with intense and lengthy wildfires is forcing California and neighboring states to make difficult (and costly) decisions concerning environmental governance over water allocation.

What is environmental governance in human-environment interactions?

As you’ve seen from prior sections in this article, human-environment interactions — just like human-human interactions — function like coupled exchanges. As people influence each other during interactions, so, too, do humans and the environment affect each other.

In other words, humans affect the environment during their interplays, and the environment impacts humans in turn.

It is a two-way street.

In cases where nature exerts its power and humans are forced to work within the parameters set by nature, people must address questions about how to manage the environment. If not, humans could get overwhelmed. They and their societies would suffer immensely.

So, issues of environmental governance come into play.

In other words, questions about who makes the decisions and sets the policy about environmental matters come into sharp focus and demand immediate attention.

Examples of environmental issues that people must sort out and resolve include (in the cases discussed in the previous section):

- Should forests be thinned to prevent rapid transmission of flames?

- Should there be controlled burns during other times of the year as a way to limit uncontrolled wildfires later?

- Should utility companies pay the billions in damages from wildfire if they have been found negligent in making repairs or upgrades to faulty equipment?

- Do waterways need to be widened or deepened to prevent flash flooding? Who should pay for this?

- Should entire towns too close to flood-prone waterways be relocated?

- Is a “zero-Covid” policy effective in controlling viral transmission? Should governments control citizens so stringently?

- How long should masking, testing, and other methods be in place before the virus is sufficiently contained?

- How should water be allocated between farmers, ranchers, and residents? Which segment of the population should get the most?

- Should governments enforce water rationing or mandate wastewater recycling for certain reuses?

The multiple stakeholders (farmers, ranchers, utility companies, private citizens, etc.) in these and similar situations of environmental governance will answer these and similar questions differently. Yet they all must be addressed and decided upon before the next natural catastrophe befalls humans.

If not, the consequences could be even more dire.

Furthermore, it’s important to remember that environmental governance concerning human-environmental interactions is even more complex than the above questions suggest.

In order to make such decisions about environmental governance, environmental constraints that limit the options available to decision makers and stakeholders must be taken into account. There are external factors (land features, climate, availability of water sources, etc.) that cannot be dismissed.

In this way, too, the environment has the upper hand in these (and many other) types of human-environment interactions.

There is no getting around it.

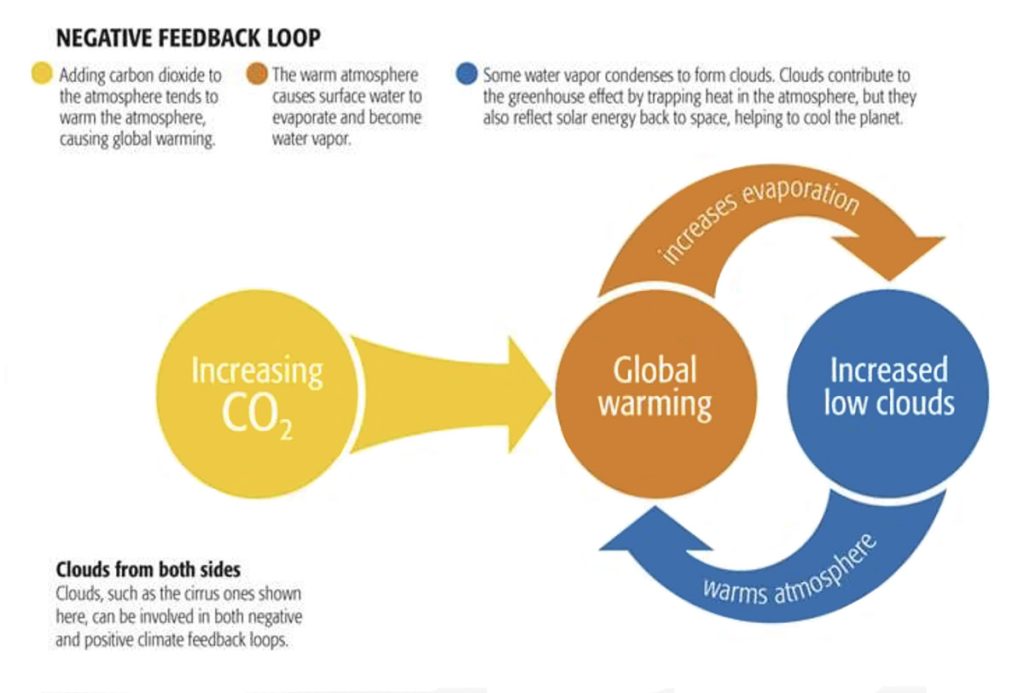

Keep in mind, too, that whatever policy decisions are formulated to govern human-environmental interactions, they will further affect those social-ecological relationships. The two are inextricably coupled together through positive and negative feedback loops.

There may be expanded impacts from the governance decisions impacting:

- Ecosystems

- Species

- Waterways

- Climate

Affecting just one part of the environment from the list above will undoubtedly impact other parts as well. All things in nature are inter-connected.

Insofar as humans are a part of nature, they, too, are impacted by human-environment interactions.

What does ethics have to do with human-environment interactions?

Readers may notice from the list of questions in the previous section that many of them began with the word “should.”

This word signifies that the question is a moral one, concerning how humans ought to act.

Although scientific facts may help inform decision making concerning environmental governance in terms of human-environment interactions, they’re not enough for a full response to the question.

In ethics, the stand off between facts and values is called the “is-ought dilemma.”

When it comes to human-environment interactions in the 21st century, there is a growing list of ethical issues that humans across the globe must collectively and individually respond to.

Some of the realms of human civilization touched by human-environment interactions include:

- Politics

- Economics

- “Development” (of poor countries)

In these and other areas, fundamental questions concerning equality and justice persist.

For example, since only a handful of wealthy individuals (the “ultra-rich”) and less than 100 fossil fuel companies in the world are responsible for the majority of carbon emissions, serious questions face humans today about:

- moral responsibility;

- who should make lifestyle changes in order to reduce emissions;

- (3) who should pay for the environmental and climate damage experienced by innocent people in poor countries because of those lifestyles supported by fossil fuel companies.

Glaring income disparities in countries around the world raise issues about climate and environmental justice.

Ironically, there is plenty of evidence that Indigenous peoples have done the most to preserve and protect nature through their human-environment interactions for centuries.

Today, Indigenous peoples represent 5% of all humans on Earth.

Yet over 200 Indigenous were killed in 2020 while defending the land and ecosystems that have enabled them to thrive through millennia.

With them dies Indigenous knowledge about maintaining healthy human-environmental interactions.

Incidentally, this entire discussion on human-environment interactions as it pertains to climate and the environment applies equally well to global Covid-19 vaccine equity.

If countries decide to do little or nothing to change the status quo, especially regarding our climate crisis, it is likely that humanity won’t make it to the 22nd century.

What is certain, based on the best climate models, is that unless carbon emissions are drastically cut by at least 45% this decade, Earth in 2100 likely will not resemble the planet we call home today.

This is not over-exaggeration.

Collective responsibility in human-environment interactions

A pressing ethical dilemma known as the “tragedy of the commons” occurs in human-environment interactions.

In economic terms, this dilemma results from externalizing the costs of manufacturing or of fossil fuel extraction while a few companies and their shareholders reap huge profits.

The natural resources shared by all — held “in common” — are used up or polluted by a few.

While countries have precisely defined borders, water pollution and air pollution do not. All people suffer, especially the poor and minorities.

Thus, it’s understandable that Canada would be angered at its maple trees and pristine lakes dying from U.S.-generated air pollution causing acid rain.

Or African countries facing the worst effects of an anthropogenic climate crisis with millions on the verge of famine due to extreme, prolonged drought, believe that the United States is largely to blame and should help them adapt — let alone survive.

Source: Flickr / Katrina Charles / REACH

So, in these and similar circumstances, humans have to address human-environment interactions collectively — across borders.

Sadly, despite “globalization,” cooperation among nations is rare. But it is absolutely essential for remedying the global climate crisis.

The supposed legally binding 2015 Paris Agreement is not enough to curb our climate crisis as recent “natural” catastrophes the world over — and increasing carbon emissions — make clear.

Few signatories are actually reducing their carbon emissions today. In fact, the opposite is occurring along with an alarming number of new oil and gas projects planned for the near future.

Equitable Covid-19 vaccine distribution as a way to control the pandemic is another case in point as mentioned previously.

Individual responsibility in human-environment interactions

Large corporations which profit from extracting environmental resources to make huge profits while externalizing costs through the tragedy of the commons (see previous section), often try to shift responsibility to individuals.

Thus, Shell Corporation, a global fossil fuel company, introduced the notion of a personal carbon footprint. With this idea, individual consumers are tricked into blaming themselves for our climate and ecological crises.

“Maybe I’m not doing enough to help heal human-environment interactions,” is the mindset intended by a focus on personal carbon footprints.

However, the monumental alterations and modifications to the environment made by big businesses and governments — especially since the start of the Industrial Age around 1800 — are not the responsibility of individuals.

While it is true that individuals are complicit in environmental degradation — including our climate crisis — this is so only through purchasing and using the products dependent on fossil fuels for their manufacture.

In many cases, until very recently in human history, humans have not been given a choice between buying and using:

- Renewable energy vs. nonrenewable energy

- Sustainable products vs. single-use products

- Organic foods vs. foods produced with chemical fertilizers and pesticides

Despite significant upfront costs for residential renewable energy, the costs are coming down.

The same can be said for many sustainable products and organic foods.

So while it’s helpful to consider your personal environmental footprints and make lifestyle changes, keep in mind that systemic changes are necessary to improve human-environment interactions permanently.

To assist in the process of making systemic changes to energy and food production, for example, individuals can get involved politically by running for office or electing candidates who support environmental issues and are willing to legislate in favor of the environment and climate.

Changing the politics that maintains the status quo and is destroying the environment and the climate in the name of wealth creation for the elite only is a major part of the way to equilibrate human-environment interactions.

Then — and only then — can people truly say they’ve achieved a sustainable way of living on Earth and coexist in harmony with nature through healthy human-environment interactions.

How can humans improve human-environment interactions?

Experts predict that if people do not make drastic improvements in human-environment interactions before 2030 regarding fossil fuel use and drastically reduce emissions, children today may suffer terribly in a hostile environment and climate not conducive to human existence by the time they are in their 60s and 70s.

Let that sink in for a minute.

That’s less than eight years from now.

Fortunately, there are several instances of businesses or groups actively engaged in restoring the balance in human-environmental interactions. These may be used as models for others to emulate.

When they are, a greater number of improvements to human-environment interactions will result.

Here are three examples:

1. Ocean fisheries and human-environment interactions

To prevent overfishing and depletion of fish stocks, researchers documented cases of the Individual Fishing Quota (IFQ) program on the West Coast of the U.S. that incentivized fishers to harvest fish sustainably using principles of a rights-based fishery (RBF) also called a “secure-access system” or a “catch-share” program.

The IFQ program came about as a result of national legislation that prohibits overfishing and necessitates rebuilding stocks through a catch limit. If not followed, the fishers would suffer severe consequences.

In this program, there is no “race to catch.” Rather, each fisher is allotted a certain share of the catch in advance, or a specific area in which to fish.

Source: Flickr / Dennis Jarvis

As a result of these programs:

- Reductions in bycatch

- Fewer depleted species

- Increased profits for fishers

- Establishment of no-fishing zones that are respected

- Elimination of the catch of nontarget species

- Fishing only under safe weather conditions

Thus, the human-environmental interplays between the fishers and the fish in their marine ecosystem are healthy, balanced, and sustainable.

2. Tropical biodiversity and agriculture in human-environment interactions

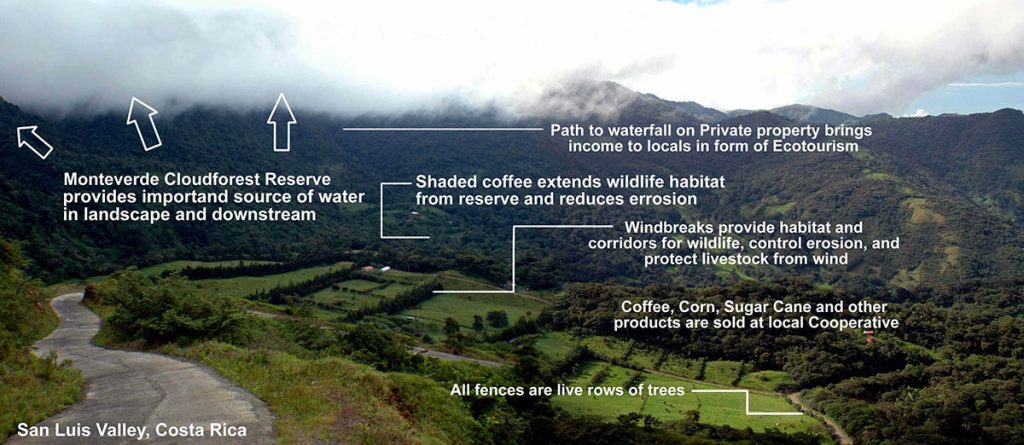

Researchers in Costa Rica and in Brazil documented environmentally sound practices that maintained natural forest ecosystems and their inherent biodiversity along with agriculture.

In Costa Rica, nearly half of forests are integrated with farms. This arrangement preserves the biodiversity of the forest ecosystems while providing food for the local human community.

The success of this way of farming depends on economic incentives (that is, monetary compensation) to farmers. In this manner, the community shows its appreciation for the preservation of the ecosystem services these farmers make possible through their land stewardship practices.

Source: Wikimedia / Nathan Dappen

A similar scenario exists in certain parts of the southern Brazil highlands. Farmers develop a mosaic of agricultural lands and silviculture (cultivation of trees) embedded in the preservation of natural grasslands and forests.

Economic incentives for the farmers, representing the high valuation of maintaining and preserving natural landscapes and ecosystem services, are key for the success of this type of human-environment interaction.

3. National Carbon Exchange in human-environment interaction

Using AI, Zack Parisa and Max Nova, co-founders of the National Carbon Exchange (NCX), developed a database of every tree in U.S. forests. Size, species, and precise location identified and cataloged.

NCX provides economic incentives to farmers and landowners with both large and small amounts of forest acreage to maintain the forests on their property through carbon offsets purchased by corporations.

Although buying carbon offsets as forest credits to enable companies to continue to pollute isn’t the ultimate answer to our climate crisis, high-quality carbon offset programs may result in a net reduction of carbon emissions.

As a result, the forests thrive. Wildlife in those ecosystems flourish. The forests continue to act as carbon sinks.

Win. Win. Win.

The takeaway message from these human-environment case studies is that when plans are put in place in cooperation with local stakeholders, and economic incentives for the maintenance of natural systems are present, human-environment interactions can thrive for both people and the environment.

Top ten ways to improve human-environment interactions

With the goal of improving human-environment interactions, this article surveys several major human impacts on nature. Energy production and land use are the most central issues in most human-environment interactions.

Based on the analyses presented here, the race against time to maintain a habitable Earth requires (among many other things):

- Switch to 100% renewable energy

- Decarbonize transportation to 100% electric (homes, too)

- Increase efficiency of renewable energy generation, HVAC, and appliances

- Invent a eco-friendly alternative to plastic — the scourge of oceans and marine life

- Discover methods of energy production and storage that do not require precious mineral extraction

- End deforestation for livestock and palm oil

- Stop new construction that encroaches further on ecosystems and wildlife habitat, potentially leading to pandemics

- Convert to regenerative agricultural practices and agrivoltaics to eliminate fossil fuel-derived pesticides and fertilizers as well as to restore healthy soil

- Reduce or eliminate meat and dairy from your diet

- End food waste by buying less, supporting local farmers, and composting

FAQs on human environmental interactions

Human-environment interactions are complex. This article describes many aspects of them. If you still have questions, these FAQs may help answer them.

Is there “built-in” future global heating from today’s carbon emissions?

Many media reports suggest that carbon dioxide emissions will have long-lasting, “locked in” effects on global heating by continually raising the temperature long after they’ve been released from fossil fuel burning.

However, recent research — as well as research published in 2008 — throws doubt on the truth of this speculation. Most scientists believe that global heating will stop once net zero carbon dioxide emissions is achieved.

However, the situation is not that simple. The long-term effects of other greenhouse gases (notably methane and nitrous oxide) are not well understood.

Furthermore, the temperature is expected to remain high for hundreds of years after all anthropogenic carbon emissions have ceased.

This is partly because of the influx of “natural” methane from permafrost thawing (already widely occurring due to human-caused global heating).

Also, the reduced ability of the oceans to absorb more carbon dioxide (since it’s already close to capacity) means CO2 will remain in the atmosphere to sustain the higher temperature.

In order to reverse the trend of global heating — which will take hundreds of additional years after climate stabilization under net zero conditions — there must be a net negative of carbon emissions on a planetary scale.

What does sustainability have to do with human-environment interactions?

Central to the complex notion of sustainability is balanced coexistence among humans and other animals, integrated in or dependent on multiple ecosystems, including urban ones.

So, human-environment interactions — through social-ecological couplings — are foundational to sustainability.

Above all, the concept of sustainability refers to humans’ ability to maintain a steady supply of natural resources through healthy ecosystem functioning for future generations through wise use today.

Human stakeholders involved in human-environmental interplays or impacted by them (that is, both living and future generations) debate whether and to what degree they should enact the following with the goal of achieving genuine sustainability:

- Preserve large segments of nature, making them off limits to humans

- Restore natural ecosystems to how they were in pre-industrial times

- Make reparations to Indigenous peoples, including returning their lands and waterways to them or removing oil and gas pipelines that run through them

- Reject capitalism in favor of democratic socialism

- Create a circular (non-linear) economy

- Place a ceiling on wealth accumulation

- Ensure a basic income to all people

- Redefine gross domestic product (GDP) to center on health and happiness in a clean environment instead of on money

Unfortunately, the environmental components of all human-environment interactions do not speak any human language. They cannot defend themselves in a court of law. Ecological systems cannot speak up for themselves in the debates over the issue expressed in the points above.

Human defenders — and many nonprofit groups — of the land, water, wildlife, ecosystems, etc. voice their concerns on behalf of the environment. Some advocate for legal standing of rivers, ecosystems, animals, etc.

Defining a river, for example, as a legal person will bestow rights that must be respected in a court of law.

Similarly, calls for making environmental degradation an international crime of ecocide are based on elevating the environmental side of human-environmental interactions.

These legal strategies are intended to make human-environment interactions more balanced. Their ultimate goal is genuine and permanent sustainability.

Bottom line on human-environment interactions

Ever since the dawn of industrialization, humans have dramatically reshaped the world through human-environment interactions.

Except for a few cases, this human-caused transformation has resulted in astonishing levels of environmental devastation accomplished at alarming rates.

The biggest driver of the environmental damage evidenced everywhere on the planet is the burning of fossil fuels.

Because the carbon emissions released today will continue to wreak havoc on both human civilization and the planet for generations to come, it is imperative to stop burning fossil fuels as soon as possible.

In order to continue living on a planet conducive to human civilization, humanity must quickly transition to renewable energy. Also required is a moral shift in values toward sustainable living and away from capitalistic consumption.

Accomplishing these goals through productive human-environment interactions will ensure human survival in functional and thriving planetary systems — physical, ecological, and biological.